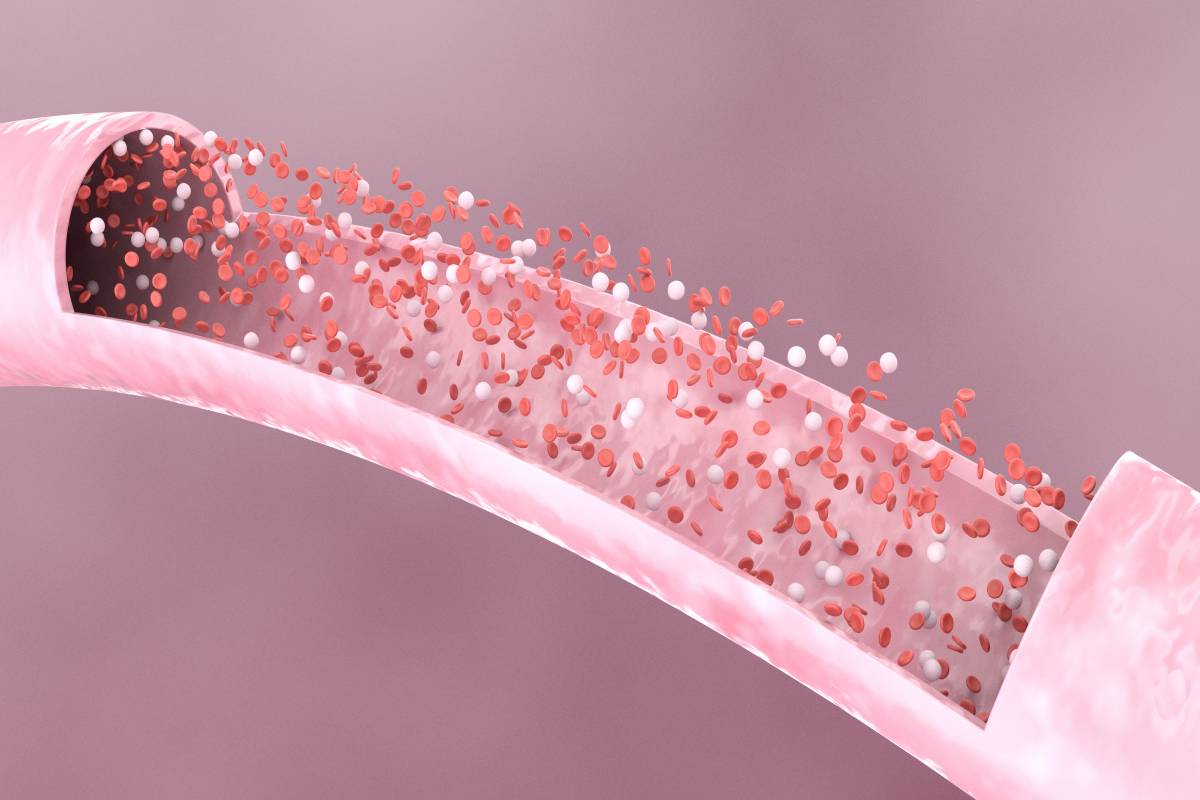

Alcohol is a widely consumed substance that has effects on multiple parts of the body, including the blood and the immune system [1]. One of the components of blood that is affected by alcohol is platelets, which are small cells that help form clots and stop bleeding [2]. Platelets are essential for wound healing and preventing excessive blood loss during and after surgery [3]. However, alcohol use can interfere with the normal function and number of platelets, increasing the risk of bleeding complications and infections after surgery [3].

Alcohol use can have both acute and chronic effects on platelets, depending on the amount and frequency of consumption, with different impacts on surgery [2,4]. Acute intake, or binge drinking, can cause a temporary increase in platelet count and activity, making the blood more prone to clotting [4]. This can increase the risk of thrombosis, or blood clots, in the arteries or veins, which can lead to stroke, heart attack, or pulmonary embolism [4]. On the other hand, chronic alcohol intake, or heavy drinking, can cause a decrease in platelet count and function, which can make the blood less able to clot [2]. Consumption of alcohol is associated with an increased risk of bleeding, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract [5]. This is due to the potential damage to the lining of the stomach and intestines [5].

Alcohol use can also affect the production of platelets in the bone marrow and their clearance from the spleen and liver, which can have different implications depending on the type and timing of surgery [2]. For elective surgeries, such as cosmetic or orthopedic procedures, it is advisable to abstain for at least a week before the surgery to normalize the platelet count and function [6,7]. For emergency surgeries, such as trauma or appendicitis, any available information on alcohol intake is highly valuable, as alcohol can affect the choice of anesthesia and the need for blood transfusion. Alcohol can also interact with some medications that are used before or during surgery, such as antibiotics, painkillers, and anticoagulants, which can alter their effectiveness and safety [8]. Drinking immediately after surgery has adverse effects on platelets and wound healing by impairing the inflammatory response and the formation of new blood vessels essential for tissue repair and regeneration [9]. Alcohol consumption suppresses the immune system and elevates the risk of infection, potentially leading to delayed wound healing and increased scarring [1,9].

Due to the potential for complications if platelets are compromised, it is advised to avoid or minimize alcohol use following surgery until the wound is fully healed and the medication has been discontinued [10]. The duration of abstinence may vary depending on the type and extent of surgery, the patient’s medical history, and the surgeon’s recommendations. Generally, it is advisable to avoid alcohol for 5-6 weeks after surgery and to limit the intake to no more than one drink per day for men and half a drink per day for women after the wound is healed [10]. Alcohol consumption should also be monitored and reported to the health care provider, as it can affect follow-up tests and the evaluation of the surgery outcome.

Alcohol use can have significant effects on platelets and increase the risk of bleeding complications and infections and impair recovery and surgery outcomes. Patients who plan to undergo surgery or have recently had surgery should be aware of the potential impact of alcohol on their platelets and their health. Following the guidelines and advice of healthcare providers can help improve the chances of a successful and safe surgery and a faster and smoother healing process.

References

- Ballard H. S. (1997). The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol health and research world, 21(1), 42–52

- Biolato, M., Vitale, F., Galasso, T., Gasbarrini, A., & Grieco, A. (2023). Minimum platelet count threshold before invasive procedures in cirrhosis: Evolution of the guidelines. World journal of gastrointestinal surgery, 15(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i2.127

- Bode, C., & Bode, J. C. (1997). Alcohol’s role in gastrointestinal tract disorders. Alcohol health and research world, 21(1), 76–83.

- Chapman, L., Ren, T., Solka, J., Bazzi, A. R., Borsari, B., Mello, M. J., & Fernandez, A. C. (2023). Reducing Alcohol Use Before and After Surgery: Qualitative Study of Two Treatment Approaches. JMIR perioperative medicine, 6, e42532. https://doi.org/10.2196/42532

- Fernandez, A. C., Chapman, L., Ren, T. Y., Baxley, C., Hallway, A. K., Tang, M. J., Waljee, J. F., Friedmann, P. D., Mello, M., Borsari, B., & Blow, F. (2022). Preoperative alcohol interventions for elective surgical patients: Results from a randomized pilot trial. Surgery, 172(6), 1673–1681. nhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2022.09.012

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of dental research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125

- Locatelli, L., Colciago, A., Castiglioni, S., & Maier, J. A. (2021). Platelets in Wound Healing: What Happens in Space? Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology, 9, 716184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.716184

- Piano M. R. (2017). Alcohol’s Effects on the Cardiovascular System. Alcohol research : current reviews, 38(2), 219–241.

- Sarkar, D., Jung, M. K., & Wang, H. J. (2015). Alcohol and the Immune System. Alcohol Research : Current Reviews, 37(2), 153–155.

- Weathermon, R., & Crabb, D. W. (1999). Alcohol and medication interactions. Alcohol research & health: the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 23(1), 40–54.